09. November 2022

PD Dr. Anna Wiehl

The COVID-19 pandemic can be seen as not only a heavily digitally experienced but also a digitally documented crisis in recent history. Especially in the first phase of lockdowns, numerous documentary practices emerged collaboratively coping with the crisis, sharing one's individual stories and of thereby – more or less deliberately – contributing to a polyphonic archive of vernacular stories. Various participatory projects have been launched to provide a platform for the contributions of participants from all over the world. This led to a diverse corpus of micro-narratives which not only document times of unforeseen transformation, but which also reflect the complexity and non-simultaneity of the pandemic around the globe.

Taking two paradigmatic cases – Corona Haikus (Gaudenzi, Tabares-Duque et al., 2020) and Corona Diaries (Panetta, Burgund, Burke et al., 2020) – my colleagues Jasmin Kermanchi, Sandra Gaudenzi and I examine different dimensions of these communicative, artistic and at the same time documentary, archival practices. We address questions ranging from the narrative and poetic audio-visual form to ethic and economic concerns when choosing a social media platform; we discuss issues ranging from the analysis of layers of interactivity, participation and co-creativity in collaborative projects to agile ethics of co-creation and governance; and we try to identify differences and similarities between projects, deducing which sometimes various functions they had at a time and which needs they fulfilled.

Both projects – Corona Haikus and Corona Diaries – show that right from the beginning of the crisis there was an awareness that the COVID-19 pandemic was a historic moment that needed to be documented for future generations. Or, as Astrid Erll puts it: "It is the first worldwide digitally witnessed pandemic, a test case for the making of global memory in the new media ecology" (2020, p. 867).

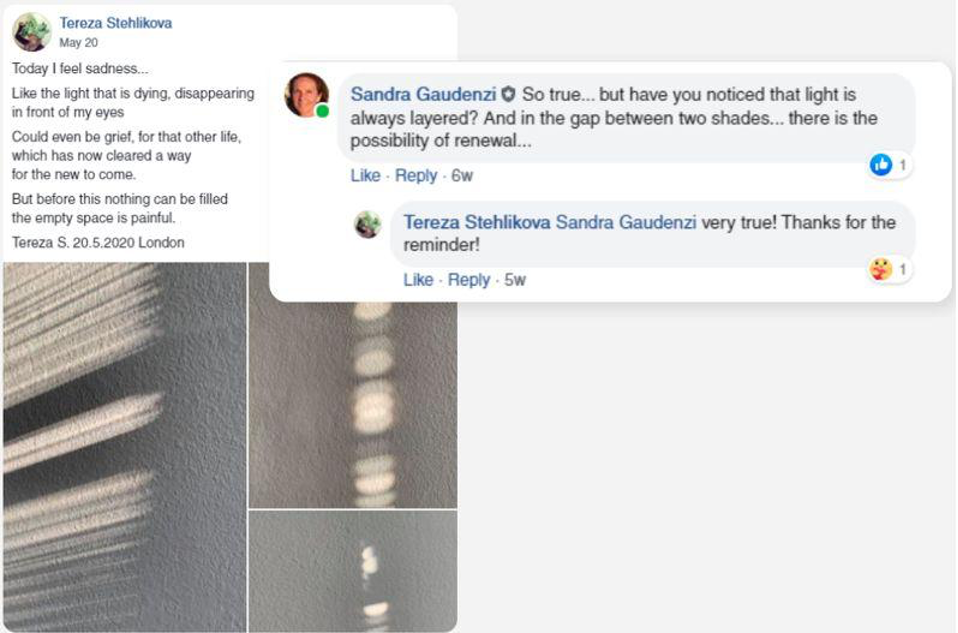

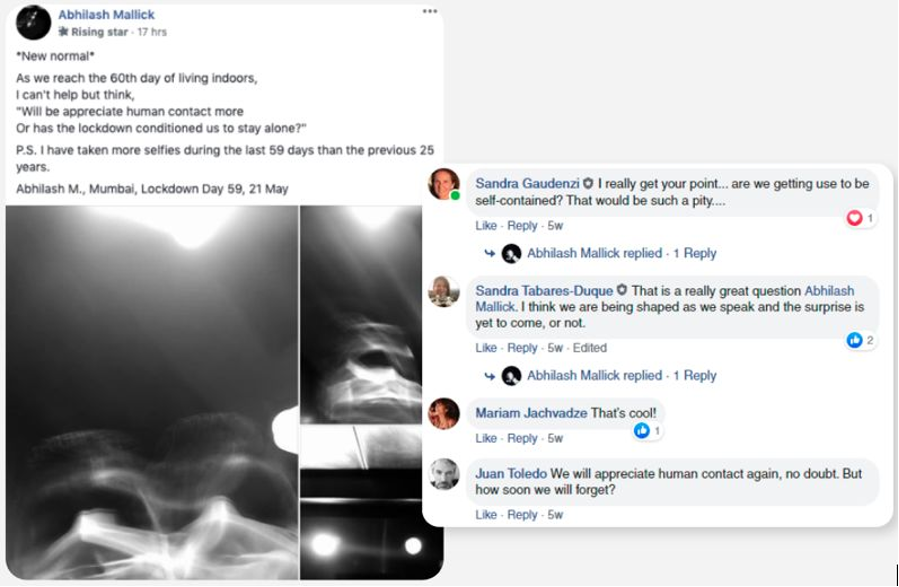

Corona Haikus started as a Facebook group and later migrated to a curated archive. In a very short time, the project built a considerable community of regularly posting contributors. What makes the project outstanding is not only the fact that itcombines poetic textual and visual forms of documenting (working on the principle of visual haikus, i.e. visual poetry), but that it also encourages the participants to engage in a dialogue on possible readings of posts. In this sense, they appropriated a well-established platform – Facebook – and exploited the affordances of procedural, dialogic networked social media. Thus, due to its networked ontology, on a meta-level the corpus offers itself various interpretations of the epistemology of singular posts as well as of meta-narratives that evolved on the network.

The project gathered an international community of more than 1,000 people coming from 30 different countries all over the world. Especially during the very strict measures in the first phases of lockdowns, the community co-created a space of documentation of their lockdown feelings and experiences. In this space, everybody, including the initiators themselves, experimented with different forms of expression and hence coping as well as contributing to a kind of polyphonic, global collective memory in the digital. Thus, participation and co-creation are certainly one key concept within the project, which extended citizen science driven public history making into the digital. Furthermore, the community decided on timings within in the project – e.g. the moment in time when to say goodbye to the co-creators in the project and to retreat from the engagement in the Corona Haikus project when the pandemic ebbed away. And even when a part of the visual haikus posted in Facebook was migrated to and archived on the coronahaikus.com website as a collectively curated space, it was again a community decision. This strategy of collective archiving and 'doing history' allows for a healthy plurality of perspectives through deep listening and shared decision making.

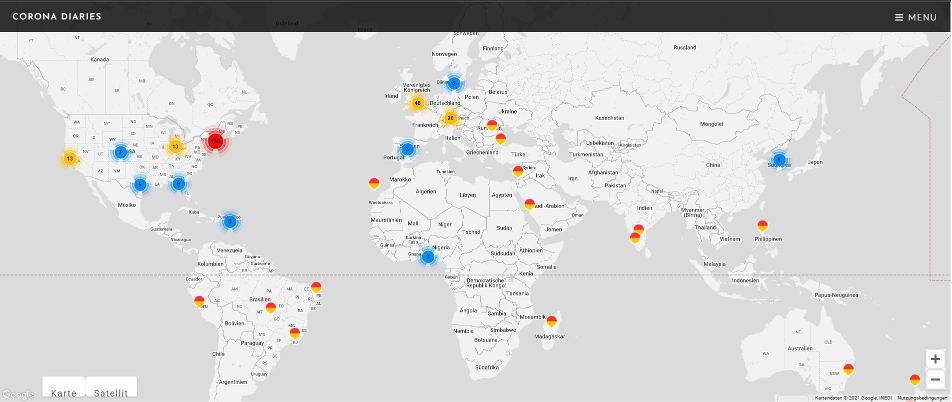

Similarly, the second project examined, the audio-based Corona Diaries, promotes the creation of a hyper-global networked narrative, starting from the premises that diaries in general provide a "valuable window into [a] period" (Miller 2020). This holds even more so for polyphonic, pluriperspective 'diaries' which include the reflections and experiences made by people from all over the globe.

Along with GPS metadata, voice-recordings of personal experiences and reflections could be posted on the site. What makes this project special as a corpus for research is the fact that it experiments with the spatial dimension of social media archives: due to the GPS data, the archive of recordings unfolds as a polyphonic network of narratives laid over the entire globe.

The Corona Diaries project is designed as an open source project, i.e. the audio content can be downloaded and used under the Creative Commons license CC BY 4.0 (redistribution and remix under attribution), which is also clearly explained to the participants in the conditions of participation. In addition to the goal of serving as a long-term archive, the project had another, more short-term intention: "For now, we hope to give people a tool to express themselves and to make it accessible for others. Ideally other people will make use of it for art, journalism, or projects we can't even think of [...]" (Köppen cited in Carlson 2020). Though research projects in the field of history are not explicitly named here, the project also addresses researchers in archiving projects at universities (Panetta and Burgundy 2020).

Alongside exploring the insights social media projects such as Corona Diaries and Corona Haikus offer on the content level as corpuses for research, we also reflect on theoretical and methodological issues: How do subjective, individual experiences and collective narratives of reality relate to each other in such documentary social media projects? What role do the affordances of networkedness and networking, performativity, procedurality and interactivity play in these projects and how does this affect their analysis? Above all, however, we probe into the potential as well as the challenges of these projects and thus what one can deduce as 'lessons-learnt' when designing future projects – both with regard to corpus-orientated research taking social media archives as resources and in view of the development of interventions in doing public history.

We recognized that narrative theory addressing phenomena of collective vernacular storytelling in combination with recent discourses in the field of expanded documentary practices can offer great insight. Both strands are built on reflections from praxeological approaches in research and project design, and both put emphasis on doings – in our case doing documentary and doing history at both an individual level and a collective one.

Especially two aspects – the differentiation between various intertwined dimensions of 'the Interactive' as well as the interdependency of networkedness and networking – enable us as researchers to explore discursivity, affect and polyphonic, plurivocal, mutliperspective negotiation of urgent matters of concern in their relationality. In the projects here analysed, collective narratives about historic occurrences create spaces for negotiating events and for bringing up elements which – first as micro-(hi)stories might become part of a collective imaginary or collective memory in the digital. Thus, i-doc projects such as Corona Diaries or Corona Haikus open up spaces for community-building experiences – and this in the cases examined in a global dimension in times of a pandemic; but they also contribute to the creation of collective polyphonic, living memory.

Examining through these analytical lenses, we recognized that forms of digital collective narratives fulfil existential functions for individuals as well as communities. Anthropological, sociological or psychological narrative theories emphasise in particular the interactional components of collective storytelling and the emotional dimension with regard to self-assurance and belonging to a group. Parallels to theories of the interdependency of cultural texts, including vernacular text, collective imaginary, collective memory and identity (Assmann and Conrad 2010; Assmann 2005; Erll 2008, 2020) are obvious. Hence, we are witnessing a form of situating personal experiences within a larger historical context.

Both Corona Haikus and Corona Diaries bring together people from many different countries who have similar experiences during the pandemic; and yet, also differences and divergent interpretations have their space. The same holds for different temporalities and dynamics in global events. Nonetheless, due to the open, fluid character of the projects analyzed and the focus on doings (and also doing things differently) holds the projects together, unites the participants and thus distinguishes them as conceptualized interventions from other, more coincidental exchanges on social media.In this context, it can be assumed that often, the process of narrating and documenting (and this includes postings on social media) accompanied by individual as well as collective reflections is at least as important, if not more important, than the 'text' resulting from the process. Thus, it may even be the case that the experience of collective storytelling plays an important role in the community's self-understanding and the formation of a collective memory.

In both projects explored – Corona Diaries and Corona Haikus –, the individual narratives result in an overarching narrative regarding the pandemic, although with each new audio recording which is added, the larger story told changes. Looking at the individual narratives reveals how the collective narrative functions as a process. The projects grow into different dimensions through the addition of different perspectives on the same time period; doing documentary and doing history unfolds at the same time diachronically and synchronically, spatially and temporally.

Thus, a pluri-vocal, multi-perspective narrative develops that does not think through the pandemic in a one-dimensional way, but which leaves room for stories that may be unexpected. In the Corona Diaries, for example, the many different stories related to the pandemic are placed on an equal footing on the world map by the initiators and thus result in a multi-voiced narrative mosaic; in the Corona Haikus project, each post – including the reactions and sometimes long follow-up conversations – form micro-narratives which contribute to a bigger image. The recipients are offered a choice of different voices, not predetermined in their order, which provide them with different perspectives on the pandemic.

A final concept that should be mentioned at least briefly is that of the 'living archive' (Miles 2015): Living archives, are taking into account context and easier access; and living online archives are fluid, built for exchange, organized around everyday practices, based on an economy of exchange and communication. In this regard, projects such as the initiatives examined in this short contribution are not only 'open' in the sense that they are not managed by gate-keeping archivists through formal and informal protocols; they are also fluid as they are not so much "an institution of preservation [rather] than a series awaiting actualization" (Miles 2015).

Furthermore, especially Corona Haikus with its evolution from Facebook to a curated website illustrates a further surplus of social media sites: their communicative, discursive negotiation of issues which accompany the creation and development of the archive itself. This allows us as researchers to approach "questions around the ways in which the archive may, or may not, be able to document, archivally, its own practices in relation to the archive" (Miles 2015, p. 42).

The analytic lenses which the approaches and adjacent theories shortly sketched here have proven to be highly valuable when analysing the often dialogic, interactive, dynamic nature of social media documentary/archival projects. Yet, the central axioms of these strands of research in digital cultures do not only offer methodological and theoretical approaches to social media as resources for research; they can also be inspirational when designing participatory projects in the field of public history as social media history (and beyond).

In this context, polyphony (Zimmermann and De Michiel 2018) for example might help to approach issues raised with regard to doing public history as a participatory and multi-perspective project which enables more comprehensive and also inclusive insight into matters of concern in their interdependencies.Similarly, methods developed within projects with a strong procedural, co-creative character – also two of the key-elements in the discussion of Corona Haikus and Corona Diaries – can open venues for doing public history that really engage people and invite them to become actively involved participants. (Cizek and Uricchio 2019) What is important to remark is the fact that the maxims and the general direction of impext of the discussed issues also hold for hybrid as well as 'on ground' projects – not only for projects online.

Acknowledgement: This article is based on research conducted together with Sandra Gaudenzi and Jasmin Kermanchi.

Corona Haikus Facebook-Gruppe (2020). Initiated by Sandra Gaudenzi, Sandra Tabares-Duque et al. Online: https://www.facebook.com/groups/226094118756231/.

Corona Haikus (2020). Curated website, initiated by Sandra Gaudenzi, Sandra Tabares-Duque et al. Online: coronahaikus.com/.

Corona Diaries (2020). Initiated by Francesca Panetta, Halsey Burgund, James Burke et al. Online: https://coronadiaries.io/index.html.

Aston, Judith; Odorico, Stefano (2018): "The Poetics and Politics of Polyphony: Towards a Research Method for Interactive Documentary". In: alphaville (15), pp. 63–93.

Assmann, Aleida; Conrad, Sebastian (eds.) (2010): Memory in a global age. Discourses, practices and trajectories. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan (Palgrave Macmillan memory studies).

Assmann, Jan (2005): Das kulturelle Gedächtnis. Schrift, Erinnerung und politische Identität in frühen Hochkulturen. 5. Edition. München: Beck (Beck'sche Reihe, 1307).

Auguiste, Reece; De Michiel, Helen; Longfellow, Brenda; Naaman, Dorit; Zimmermann, Patricia R. (2020a): "Fifty Speculations and Fifteen Unresolved Questions on Co-creation in Documentary". In: Afterimage 47 (1), pp. 67–71.

Carlson, Eryn (2020): "Corona Diaries: An Open-Source Platform of Personal Covid-19 Stories". In: Nieman Reports (09.04.2020). Online: https://niemanreports.org/articles/corona-diaries-an-open-source-platform-of-personal-covid-19-stories/. Last visited 19/09/2022.

Cizek, Katerina; Uricchio, William (2019): Collective Wisdom. Co-creating media with communities, across disciplines and with algorithms. Online: https://wip.pubpub.org/. Last visited 19/09/2022.

Dahlgren, Anna Näslund; Hansson, Karin (2022): "Crowdsourcing Cultural Heritage As Democratic Practice". In: Christoph Rausch, Ruth Benschop, Emilie Sitzia and Vivian van Saaze (eds.): Participatory Practices in Art and Cultural Heritage. Learning Through and from Collaboration. Cham: Springer International Publishing; Imprint Springer (Springer eBook Collection, 5), pp. 39–48.

Erll, Astrid (2008): "Medium des kollektiven Gedächtnisses – ein (erinnerungs-)kulturwissenschaftlicher Kompaktbegriff". In: Astrid Erll, Ansgar Nünning (eds.): Medien des kollektiven Gedächtnisses. Konstruktivität – Historizität – Kulturspezifität. Berlin, New York: Walter de Gruyter (Media and cultural memory / Medien und kulturelle Erinnerung, 1), pp. 3–24.

Erll, Astrid (2020): "Will Covid-19 Become Part of Collective Memory?" In: Manuela Gerlof, Rabea Rittergold (eds.): 12 perspectives on the pandemic. Thinking in a state of exception. Berlin: De Gruyter, 46–50.

Keidl, Philipp Dominik; Melamed, Laliv; Hediger, Vinzenz; Somaini, Antonio (2020): "Pandemic Media – Introduction". In: Philipp Dominik Keidl, Laliv Melamed, Vinzenz Hediger, Antonio Somaini and Florian Hoof (eds.): Pandemic media. Lüneburg: meson press (Configurations of film), pp. 11–24.

Magnússon, Sigurður Gylfi (2003): "The Singularization of History: Social History and Microhistory within the Postmodern State of Knowledge". In: Journal of Social History 36 (3), pp. 701–735.

Miles, Adrian (2015): 12 Statements for Archival Flatness. In: Carlin, David and Vaughan, Laurene (eds.): Performing Digital: Multiple Perspectives on a Living Archive (1st ed.). London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315599960

Miller, Jen A. (2020): "Why You Should Start a Coronavirus Diary". In: The New York Times (13.04.2020).Online: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/13/smarter-living/why-you-should-start-a-coronavirus-diary.html. Last visited 19/09/2022.

Miller, Liz; Little, Edward; High, Steven C. (2017): Going public. The art of participatory practice. Vancouver, BC: UBC Press (Shared, oral & public history).

Nofal, Eslam; van Saaze, Vivian; Wyatt, Sally (2022): Online Participatory Design of Heritage Projects. In: Christoph Rausch, Ruth Benschop, Emilie Sitzia and Vivian van Saaze (eds.): Participatory Practices in Art and Cultural Heritage. Learning Through and from Collaboration. Cham: Springer International Publishing; Imprint Springer (Springer eBook Collection, 5), pp. 83–99.

Panetta, Francesca; Burgund, Halsey (2020): "Co-creating in times of corona pandemic". Webinar: I-Docs Community Conversations (02.07.2020). Online: http://i-docs.org/media/co-creating-in-times-of-corona-pandemic/. Last visited 19/09/2022.

Rose, Mandy (2017): "Not Media About, but Media With: Co-Creation for Activism". In Sandra Gaudenzi, Mandy Rose, Judith Aston (eds.): i-docs – The Evolving Practices of Interactive Documentary. New York: Wallflower, pp. 49–65.

Wiehl, Anna (2019): The ‘New’ Documentary Nexus. Networked|Networking in Interactive Assemblages. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Zimmermann, Patricia (2018): "Thirty Speculations Toward a Polyphonic Model for New Media Documentary". In: alphaville (15), pp. 9–15.

Zimmermann, Patricia Rodden; De Michiel, Helen (2018): Open space new media documentary. A toolkit for theory and practice. New York: Routledge.

Zimmermann, Patricia; De Michiel, Helen (2013): "Documentary as Open Space". In: Brian Winston (ed.): The documentary film book. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 355–365.

For more details on the methodology and the results of our research, cf.

Gaudenzi, Sandra; Kermanchi, Jasmin; Wiehl, Anna (2021): "Co-creation as im/mediate/d caring and sharing in times of crises: Reflections on collaborative interactive documentary as an agile response to community needs". In: NEXUS 19, Online: https://necsus-ejms.org/co-creation-as-im-mediate-d-caring-and-sharing-in-times-of-crises-reflections-on-collaborative-interactive-documentary-as-an-agile-response-to-community-needs/. Last visited 19/09/2022.

Kermanchi, Jasmin; Wiehl, Anna (2022): Wirklichkeitserzählungen als narrative Netzwerke. Polyphone Erzählprozesse im virtuellen Raum als gemeinschaftsbildende Erfahrungsbewältigung. In: DIEGESIS 11 (1), pp. 50–69. Last visited 19/09/2022

Wiehl, Anna; Gaudenzi, Sandra: "Closeness, co-creation and connectivity in times of social distancing and uncertainty". In: Sills-Jones, Dafydd and Kaapa, Pietari (eds.): Documentary film cultures in the age of COVID-19. New York, Frankfurt, Berlin et al.: Peter-Lang 2022 (forthcoming).

Podcast: DiD Special #1 – Corona Haikus. 10. May 2021. Online: https://kammerflimmern.podigee.io/b10-corona-haikus. Last visited 19/09/2022

Anna Wiehl has been a lecturer and research assistant at Bayreuth University, Germany, and has been a research fellow with i-docs at the Digital Cultures Research Centre, UWE, Bristol. Her transdisciplinary research focuses on documentary theory, digital cultures, and epistemic media. In 2010, she finished her PhD in the international program Cultural Encounters, and in 2019, she completed her habilitation on The 'New' Documentary Nexus. Networked|Networking in interactive assemblages. Currently, she is leading a research network on The Documentary and the Digital.